Latest Research

- 2024.12.16

- Nishiyama-Miura Group

Functionalized Polymers Recognizing Dense Amino Acid Transporters on Cancer Surfaces

In tumor cells, Glutamine and other amino acids is progressively consumed for tumor growth and survival, thus tumor cells overexpress amino acid transporters such as glutamine transporter (AST2) and LAT1 (L type amino acid transporter 1) compared to normal cells due to aberrant amino acid metabolism[1]. Thus, the development of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches based on glutamine metabolism in cancer is a very effective approach, and glutamine has great potential as an active tumor targeting molecule in drug delivery to cancer. However, weak binding affinity of glutamine to ASCT2 (Kd = 20 μM) has limited application of glutamine as a ligand molecule[1][2].

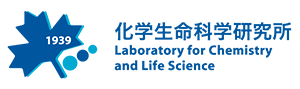

Hence, we focused on multivalent binding approach that multiple glutamine molecules interact with glutamine transporters to enhance the binding affinity. By conjugating multiple glutamine molecules into the polymer chain, the polymer could show the strong binding affinity with the surface of cancer cells where glutamine transporters are expressed at high density by the multivalent effect and work as the tumor targeting molecule, while the polymer exhibits weak binding affinity with normal cells which express low density of glutamine transporters (Figure 1).

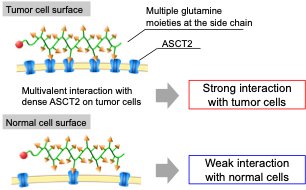

Herein, we designed glutamine-derived polymer, termed PLys(Gln)-n [n: degree of polymerization (DP)] (Figure 2a), to improve this weak affinity of the glutamine with ASCT2 by the use of multivalent effect and accomplish tumor-selective high affinity[3][4].

|

|

| Figure 1. | Illustration of the interaction of glutamine-functionalized polymers with cells |

To construct PLys(Gln)-n, we synthesized poly(L-lysine)(PLL) with different DP by NCA polymerization, and conjugated glutamine moieties to the side chain of PLL through g-amide linkage, because modification of g-amide was reported to tolerate the ASCT2-glutamine interaction[2]. A control polymer, PLys(α-Glu) (Figure 2b) was prepared via α-carboxyl amide formation to investigate the effect of chemical structure of the side chain on binding affinity. All these polymers were fluorescently labeled with Cy5 to examine their biological activity.

|

|

| Figure 2 | Chemical structure of (a) PLys(Gln) and (b) PLys(α-Glu) |

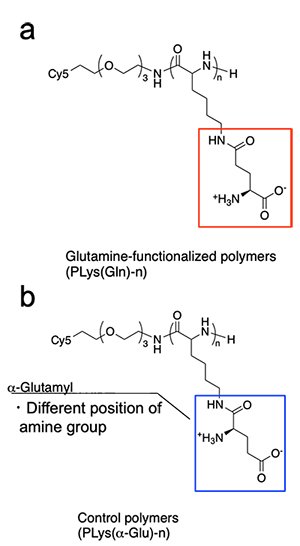

In in vitro experiment, a series of PLys(Gln)-n exhibited DP-dependent cellular uptake in A549 cells (human lung cancer cells overexpressing ASCT2)(Figure 3a). PLys(Gln)-250 exhibited 12 and 5.5-fold higher cellular uptake than PLys(Gln)-50 and -75, respectively. This DP-dependent increase in uptake is suggested to be due to multivalent binding of PLys(Gln)-n to transporters on the surface of cancer cells. PLys(a-Glu)-n also showed a slight DP-dependent increase in uptake, but its uptake was only 20% of that of PLys(Gln)-n, indicating that cancer cells recognize the Gln like structure on the polymer side chain. In addition, PLys(Gln)-100 exhibited faster and higher uptake efficacy in BxPC3 cells (human pancreatic cancer cells overexpressing ASCT2) compared to HEK293 cells (human embryonic kidney cells with low expression level of ASCT2) (Figure 3b,c). Meanwhile, PLys(a-Glu)-100 showed similar cellular uptake behaviour in BxPC3 and HEK293 cells. These results suggest that PLys(Gln)-n selective recognized cancer cells overexpressing ASCT2 on cell surface.

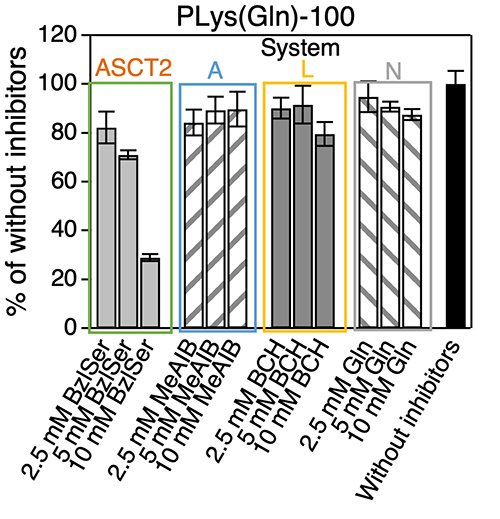

Indeed, when various glutamine transporter (ASCT2, System A, L, N) inhibitors were co-incubated with PLys(Gln)-100 and the cellular uptake into BxPC3 cells was evaluated(Figure 4). The cellular uptake of PLys(Gln)-100 was suppressed only in the presence of ASCT2 inhibitors, which indicated that the glutamine-functionalized polymer recognizes ASCT2 and is taken up. These results suggest that PLys(Gln)-100 recognizes densely expressed ASCT2 and is taken up by cancer cells.

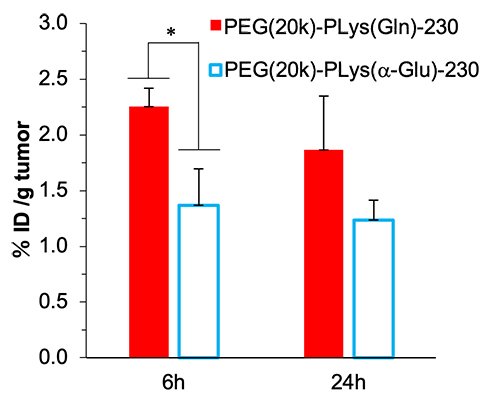

Finally, to confirm the efficacy of this glutamine-functionalized polymer in in vivo environment, by introducing PEG with a molecular weight of 20,000 into the polymers, PEG-PLys(Gln)-230 and PEG-PLys(a-Glu)-230 were synthesized and were intravenously injected to A549 cell-inoculated mice. PEG-PLys(Gln)-230 showed higher tumor accumulation than PEG-PLys(a-Glu)-230, which indicated the glutamine-functionalized polymer could recognize tumor even in in vivo(Figure 5). These results suggest that the approach of introducing multiple glutamine moieties into polymer side chains for strong tumor recognition could be a useful platform for the development of cancer therapeutic and diagnostic technologies targeting metabolic abnormalities in cancer.

|

|

| Figure 3. | (a) Cellular uptake of PLys(Gln)-n (n = 50,75, 100, 162, and 250) in A549 cells (b, c) Cellular uptake of PLys(Gln)-100 and PLys(a-Glu)-100 in BxPC3 and HEK293 cells over time |

|

|

| Figure 4. | Inhibitor study (Cell line: BxPC3 cell) |

|

|

| Figure 5. | Tumor accumulation of PEG(20k)-PLys(Gln)-230 (Inoculated cell line:A549 cell) |

Based on this concept, we also constructed a drug delivery system (DDS) targeting L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), another amino acid transporter that is overexpressed in cancer, LAT1 is an amino acid transporter that recognizes aromatic amino acids such as phenylalanine, and has recently been reported to be loaded on the surface of nanoparticles and on the side chains of polymers[5]. In addition to these aromatic amino acids, methionine (Met), a sulfur-containing amino acid, is also a substrate molecule of LAT1, and its structure is expected to be used as a LAT1 target ligand, but few DDSs with Met-like structures have been developed. Therefore, we constructed Met-modified polymers by modifying the Met to the side chain of polymers and evaluated their functions, and we found that the polymer has selectivity for LAT1 and can rapidly and selectively accumulate on tumors even in in vivo[6].

Thus, the strategy of introducing multiple amino acid molecules into the side chains of polymers is a useful approach in the development of DDS for cancer-targeting molecules, and further development is expected.

Reference

| [1] | Jin, L., Alesi, G. N. & Kang, S. Oncogene,35, 3619-25 (2016). |

| [2] | Srinivasarao M., Galliford CV.1 & Low PS., Nature Rev., 14, 203-219(2015). |

| [3] | Yamada N., Honda Y. & Nishiyama N., et al., Sci. Rep. 7,.6077(2017). |

| [4] | Honda Y. & Nishiyama N., et al., ACS Appl. Bio Mater. , 4, 10, 7402-7407 (2021). |

| [5] | Nomoto T. & Nishiyama N., et al., Sci. Adv. 6 (4) eaaz1722 (2020). |

| [4] | Guo H., Nomoto T. & Nishiyama N., et al., Biomaterials 293, 121987 (2023). |